“Given our defence and economic assistance burden, the underlying balance of payments of the United States is in basic disequilibrium and likely to get worse rather than better […]. It is only in an atmosphere of crisis and disturbance that [. . .] important changes in the policies of European countries and Japan can be brought about. The response to “crisis” is an “opportunity”.

The U.S. Under Secretary of the Treasury for international monetary affairs Paul Volcker to President Nixon, Washington, May 8, 1971.

“Those who dance are thought to be mad by those who see them and don’t hear the music”.

Wrongly attributed to Friedrich Nietzsche

“Never let a good crisis go to waste”.

Attributed to Sir Winston Churchill ostensibly paraphrasing Nicolo Machiavelli

There was no shortage of epithets hurled at Donald Trump’s declaration of a global tariff war on his so-called “Liberation Day”, April 2nd. Stock indices have plunged, volatility spiked and economists, the media and big Wall Street bosses rushed to decry the move as “idiotic”, calling it “madness”, a “fatal error” and a “clown show”. The bottom line: a bunch of narcissistic amateurs blunder through the global trade system with all the delicacy of a bull in a China shop, playing havoc on the economy.

Commentators have been fixated on rehashing of damage estimates and deriding the lack of science behind exact tariff rates as if the sanity of Trump himself (or his trade advisor Peter Navarro), the exact digits, tariff’s pauses and exemptions, compromises and bragging about other world leaders begging for mercy when they didn’t — all that white noise — really mattered.

The damage is obvious, the tariff rates themselves, as well as the formula behind them, are about as nuanced as a sledgehammer. All that visceral outrage and losses appraisal, though cathartic, miss the point and largely misread what is actually unfolding. Which is rational and, to some extent, even predictable.

Engineering a crisis

Conventional wisdom treats tariffs as tools of surgical calibration, designed to nudge trade flows preserving the trade system itself. Trump’s tariffs, by contrast, are not an attempt to augment or repair. They deliberately stoke uncertainty and unpredictability, pushing cross-border trade to a halt and, even more importantly, making investors flinch at the faintest thought of offshore manufacturing or globalised supply chains in the future.

They are wrecking balls, not scaffolding, and designed not to shore up the old edifice, but rather to level it entirely as something which is doomed to crumble.

It is neither an error, nor recklessness. Trump’s policies are not meant to avert disruption; they are meant to manufacture one. The crisis, which “Liberation Day” tariffs are bringing about, isn’t collateral damage. It’s the plan.

But if it’s the case, why, then, would a president, who at least appears to be hoping to avoid a bloodbath in the 2026 midterms, intentionally inflict economic pain, which, no doubt, would be attributed to his ignorance? The tariff shock patently fuels inflation and would almost certainly tip the economy towards a hard landing or an outright recession by late 2025 or early 2026. Even his own party doesn’t seem to be convinced that the gamble is justified. Trump may be many things, but he hardly fits the mould of a political martyr, nobly sacrificing himself for some long-term good. So what’s the game?

The answer is multifold.

One consideration is likely to be the belief that a major crisis is inevitable: not a question of if, but when. Bringing the painful bit forward so by the election year, 2028, the economy is already bouncing back would then sounds a reasonable strategy. The textbook rule of thumb for politicians taking unavoidable and unpopular steps is to implement the plan as soon as they get elected.

Yet is the prospect of an imminent crash credible? Until the “Liberation Day”, few alarm bells were ringing. The recessionary fears of 2022 vanished entirely, replaced first by expectations of a soft landing, and then by exuberant cheers of “no landing” at all. Riding this narrative, the stock market scaled one all-time high after another. A crisis? What crisis?

Chapter I. A crash of grey rhinos

Back in 2013 Michele Wucker, an author and prominent analyst of policy crises, coined the term "grey rhinos". Unlike unknown "black swans" popularised by Nassim Nicholas Taleb's 2007 book, grey rhinos are patently obvious, highly probable, high-impact threats that nevertheless remain dismissed and neglected in a form of collective denial, in a “Don’t look up” sort of moment.

One reason why they are ignored is their uncertain timing, an awkward fit for “quarterly thinking”. It’s painfully expensive to hedge against a threat that might not arrive for years. Any fund manager or corporate executive who goes risk-off too soon end up underperforming rivals and forfeiting opportunities. The more resident doomsayers and niche Jeremiahs cry “wolf,” the less attention they get.

Besides, if in the past the boom-bust cycles meant that a hungover would be commensurate with the scale of the party, nowadays policymakers seem to have mastered the art of keeping the party going on indefinitely, staving off downturns with ever more creative “countercyclical” tools. The tide, as in Warren Buffett’s metaphor, never goes out, so everyone feels safe to swim naked. When the music stops, just call it a “black swan” and you will get bailed out, like it happened with Swiss and American banks in March 2023.

By the mid-2020s, the upcoming ending of the music is not a single elephant in the room but rather a room packed to the rafters with a crush of grey rhinos no-one wants to see. Perhaps, the most obvious of them is to do with business cycles.

Juglar cycles and “capacity ceiling”

When in 1862 the French economist Clément Juglar suggested that booms and busts maybe associated with waves in investment he was referring to just plants and machinery. As demand grows, businesses eventually push their existing capacity to its limits so shortages force prices higher. This prompts a race to expand and invest in new facilities amid the boom, which, in turn, leads to overinvestment and glutted markets. Prices collapse under the weight of excess supply and what began as a boom ends in a wave of bankruptcies.

Over the last 160-odd years, much has changed, and in today’s postindustrial, services-dominated economy, fixed capital may no longer dominate as much as it once did. Yet the core idea remains: once the supply side hits capacity limits, be they physical plants, infrastructure, energy, or labour constrains, an inevitable adjustment follows.

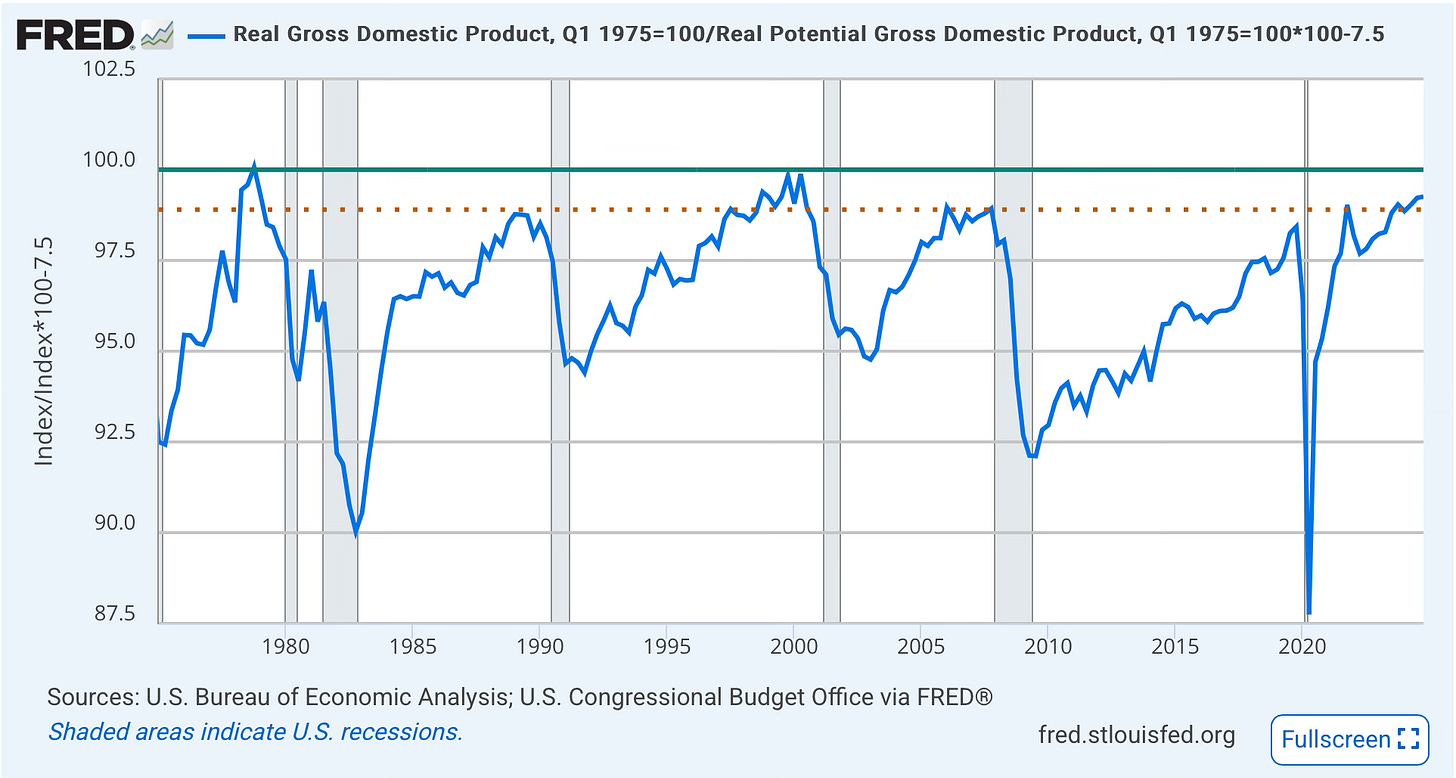

The cycles in the U.S. economy are quite distinctly visible if you look at the chart illustrating capacity utilisation: real GDP index divided by a real potential GDP index.

Over the last 50 years, every time capacity utilisation rates hit the “ceiling” there was a recession with a year or two. In the current cycle, the U.S. economy was trending to reach its maximum capacity in about by the end of this year or the first half of 2026 with elevated risks of a significant downturn somewhat in the region of 2027.

To complicate things further, in a globalised economy with few trade barriers, a country running up against domestic capacity limits doesn’t simply pause growing: it starts importing. When American demand outstrips supply, foreign goods flood in to fill the gap, and firms invest in cheaper offshore hubs to keep up with lower costs.

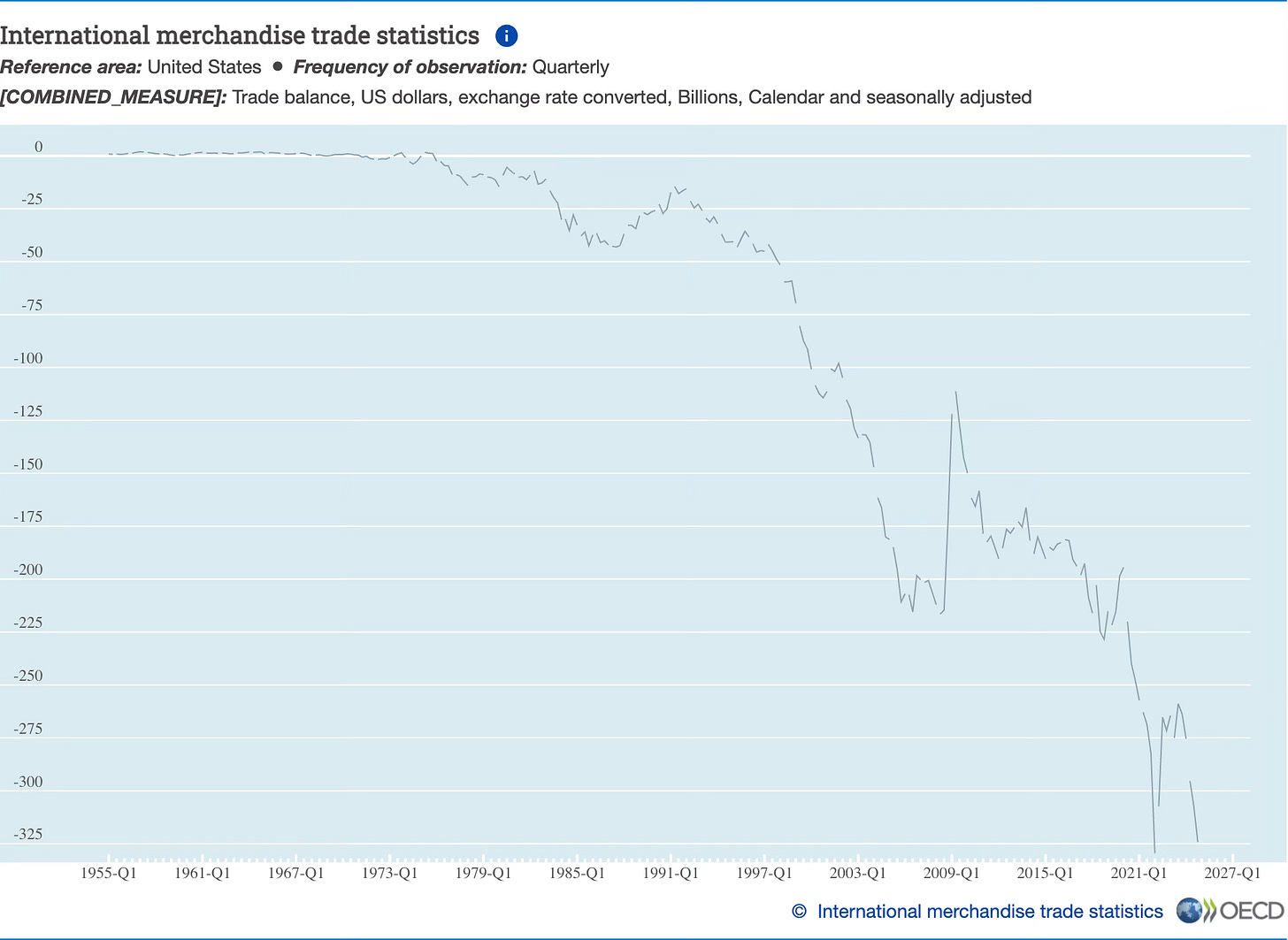

Over the past half-century, under the architecture of modern globalisation, this dynamic has caused America’s trade deficit to balloon. A rather fragile surplus in services does little to offset the yawning deficit in goods. Last year, the U.S. trade shortfall swelled to nearly 4% of GDP, a trajectory reminiscent of the mid-2000s; around 2005–06, the deficit was around 6% of GDP amid the era of great global imbalances.

Back then, America’s excess consumption was bankrolled by foreign capital, notably China’s glut of savings. Overseas investors snapped up U.S. assets from Treasury bonds to asset backed securities and equities. It didn’t age well: the binge soured into the crash of 2008, proving that the imbalances were indeed unsustainable. Now, a similar imbalance was brewing once again. Even more worryingly, while the U.S. trade gap was widening, this time around China was way less eager to fund it, having reducing their exposure to U.S. Treasuries.

Debt and liquidity

Meanwhile America’s total non-financial debt is back near its pre-2008 levels at around 250-260% of GDP, roughly $75 trillion in federal, household and corporate liabilities of the non-financial sector. That figure does’t include net liabilities of the banking sector and growing “hidden debt”, from unfunded pensions to off-balance-sheet derivatives held by hedge funds or other “shadow banking” institutions. Those, officially named “non-bank financial intermediaries”, loosely regulated, now own more of the U.S. financial assets than regulated banks do.

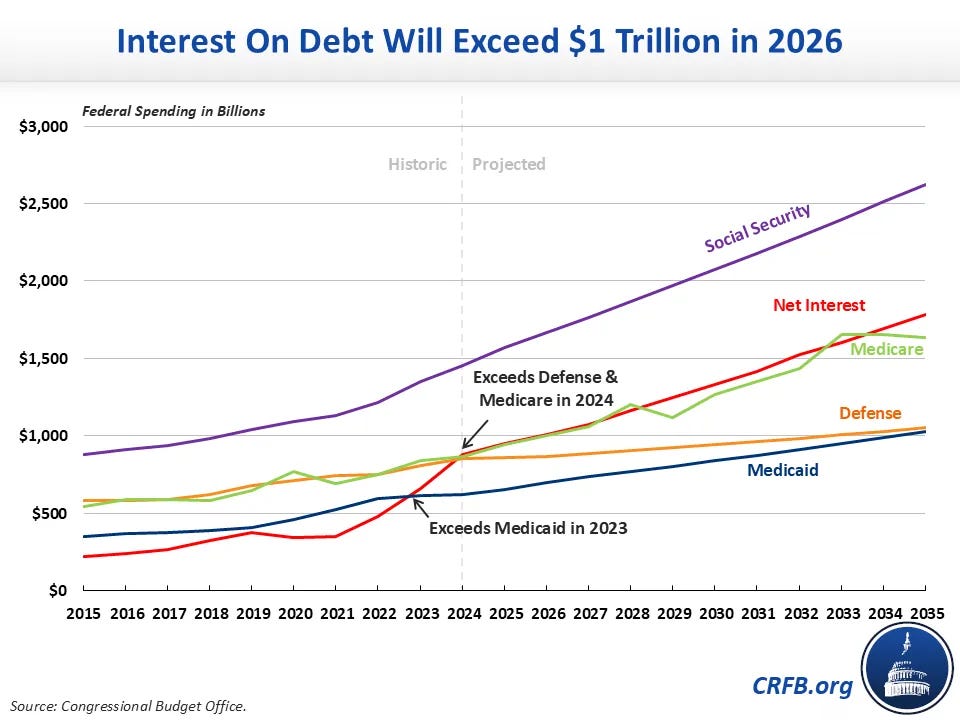

Again, around 2026-2027 most vulnerable corporate borrowers face a “maturity wall”: trillions in commercial real-estate loans and junk bonds, many issued at rock-bottom rates during the pandemic, must be refinanced. A wave of defaults seems inevitable if the Fed doesn’t slash rates to the pandemic levels. Nor is the Federal government immune: the Treasury now spends more on servicing its debt than it does on defence or medicare. None of this, of course, guarantees a 2008-style collapse, yet it translates into a critical mass promising a fully-fledged meltdown if a trigger goes off.

What could have been a trigger in around 2027 if the tariff war hadn’t started? Anything, from the burst of the stock market bubble (in February 2025 Shiller PE ratio, a busyness-cycle adjusted multiple of net profits to capitalisation, was just few tiny points below historic records of 2021 and the Dot-com bubble in 1999) to a new pandemic or an increasingly likely climate-related cataclysm. If there is a powder keg, any spark would do.

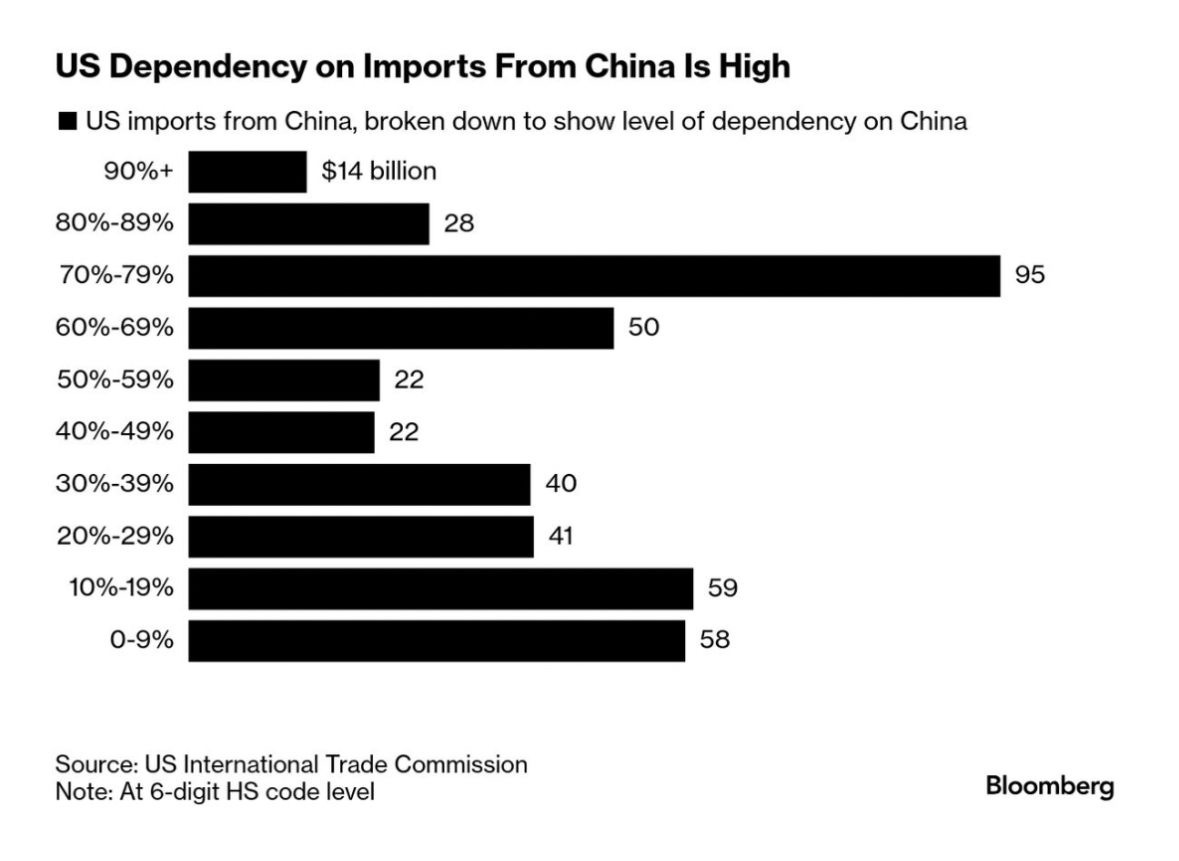

Finally, there is the China question. While military strategists and Republican leaders openly discuss 2027 as a likely point of conflict over Taiwan and forecasters predict a full scale cyber war, the U.S. economy remains deeply dependent on imports from China. That reliance dwarfs Europe’s once-heavy dependence on Russian energy before the onset of the full-scale Ukraine war on 2022.

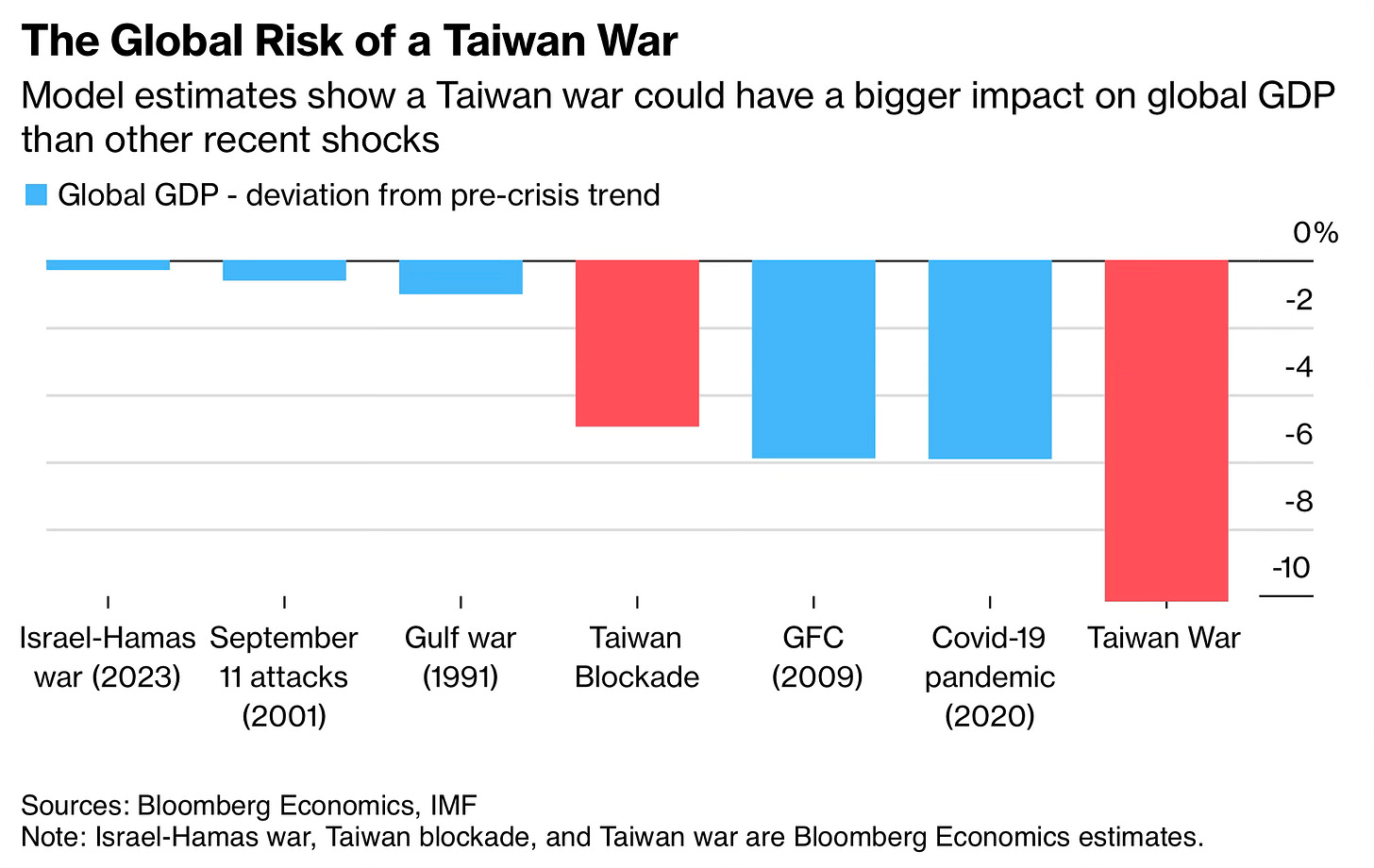

A sudden blockade or overnight interruption of supplies could prove for America truly catastrophic. Bloomberg estimates that a Taiwan conflict would lop around 10% off global GDP, more than the toll of Ukraine, Covid and 9/11 combined; with most of the burden falling on America unless it pre-emptively decouples from its potential adversary.

To sum up: a cyclical recession looming around 2027, spiralling out-of-control public and private debt with a multi-trillion-dollar maturity wall about the same time, swelling overleveraged shadow banking, and a yawning trade deficit with growing dependency on a potential military adversary. What could possibly go wrong?

Chapter II. The biggest Rhino

Joseph Schumpeter remains one of the 20th century’s most celebrated economists and the media love to use his “creative destruction” catchphrase to laud bold entrepreneurs. Yet from the World Bank and IMF to Morgan Stanley’s research desks the core of his grand theory that waves of technological innovation drive long-term cycles, including transitional downturns, is largely treated as a fringe piece of economic theory, certainly not as a tool to predict recessions. Indeed, plotting those “mysterious” half-century “Kondratieff waves” on the timeline is seen as something bordering on astrology.

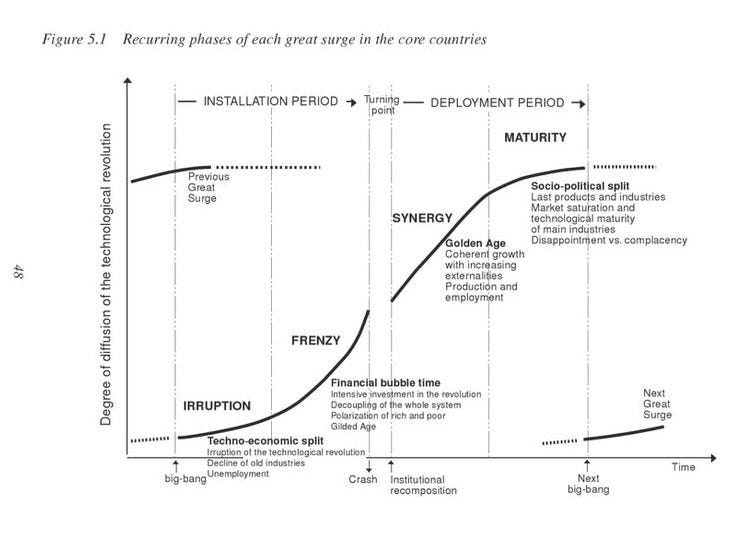

Yet 25 years ago, Carlota Perez, a British-Venezuelan neo-Schumpeterian economist, was bold enough to still follow that long tradition, including Gerhard Mensch and David Gordon, and give those long-wave theories a more practical twist. In her 2002 book, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital, she puts the concept of Kondratieff waves to the test by mapping them onto long-term data.

She found that each 50–60-year cycle follows an S-shaped curve, overlapping at its start with the tail of the previous wave and at its end with the inception stage of the next. Each of these long surges begins with a fundamental technological breakthrough (think steam power, steel or internal combustion engines) which reshapes not just entire industries but the whole socio-economic system, political institutions, the global economy architecture and the division of labour. Moreover, it also shapes the way we, economic agents, politicians and scholars alike, think about the world and make decisions. She called the waves “techno-economic paradigms.”

Watching those long-term fundamentals and looking beyond deceptive omens, like inverted yield curves or short-term sentiment swings, offers a roadmap for those who want to spot the next turning point.

According to Perez, two crises typically erupt: one when the old paradigm gives way to the new, and another around the halfway mark, when initial exponential growth hits its natural limit and bubbles, stemmed from excess savings from innovation and associated imbalances, burst.

From Hay and Steed to and Oil and Horsepower

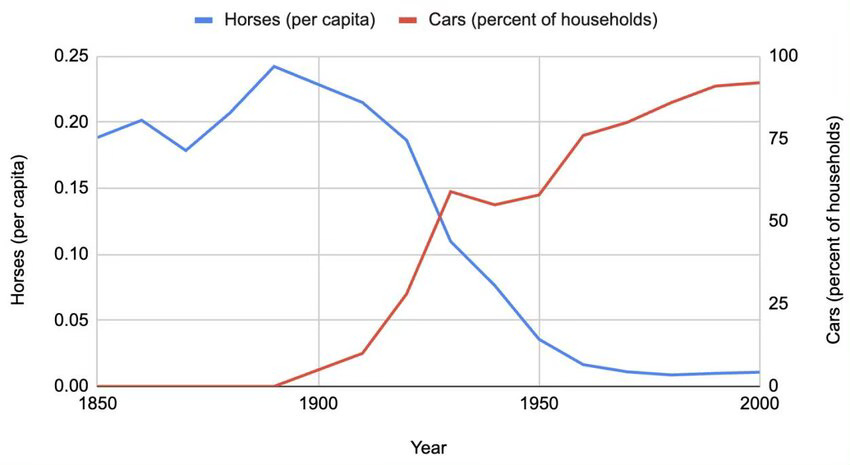

The story of one of the previous paradigms or industrial revolutions, the age of automobiles and mass production, which lasted from 1910s to the end of 1970s, makes a great example.

In 1905, roughly a quarter of the America’s agricultural output went to feeding horses. During and in the aftermath of WWI, the U.S. vastly expanded grain production to feed war-torn Europe too. Then cars and tractors took over in the 1920s, reducing demand for oats and hay just as European agriculture was recovering. The resulting glut depressed farm incomes, but it also left urban dwellers with more cash (since food, which took up a lion share of disposable income, was cheaper), a windfall that found its way into savings to fuel the car-manufacturing boom, spillover effect to all the supply chain sectors, from metals to rubber, oil rush and a roaring bull stock market.

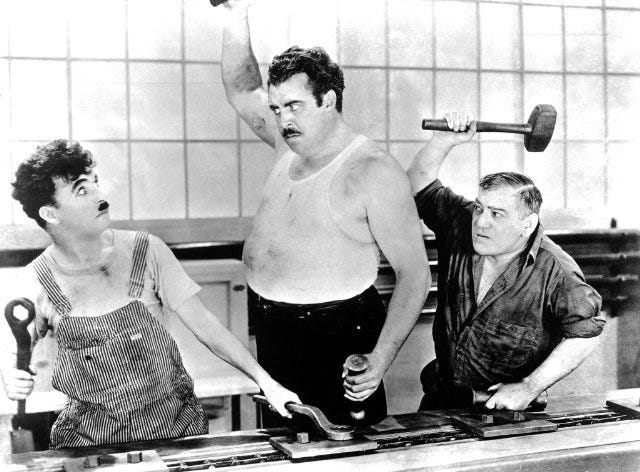

Rapid urbanisation and the spread of Ford’s mass-manufacturing eidos across main industry sectors turned society into one giant assembly line, as in Chaplin’s Modern Times. The Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset dubbed it The Revolt of the Masses: mass-standardised consumption, mass transportation, mass media, mass politics. A grand corporation, enjoying the economies of scale - the underlying idea of the paradigm - prompted the emergence of state corporatism and rise of totalitarian regimes trying to extend full political control to all their supply chains.

When that bubble of the “modern times” frenzy, underpinned by global financial imbalances, burst in 1929, it dragged the global economy into the Great Depression, disturbed cross-border trade and eventually paved the way to WWII. That was, in Perez’s terms the midway “turning point”.

After the war, the Bretton Woods system, the Marshall Plan and the Cold War “two systems” stand-off brought about what Perez calls a period of synergy in which rising incomes and stable finance spurred production, demand and global trade in the rapid post-war recovery.

It also shaped the architecture of the post-war globalisation (with the U.S. becoming the pivot of “the free world”, the source of capital, technology and military spending) and the new normal of the “big state”. When the “wave” took off in the 1910s governments would collect, spend on public goods and redistribute roughly about 5-10% of their countries’ economies output. By the time it ended in the 1970s the state would be in charge of 35-40% of GDP, running a deficit of up to 5% of GDP on the top of it.

A whole new set of public services with all their social mollycoddling capabilities (what would become the heart of the nowadays welfare state model) and regulatory institutions we now consider absolutely natural to the degree of natural rights and entitlements, taking them for granted, have been designed to deal with the shocks of the industrialisation and urbanisation stage.

Uncanny resemblance

By the 1960s, however, that cycle hit its final stage - the state of maturity.

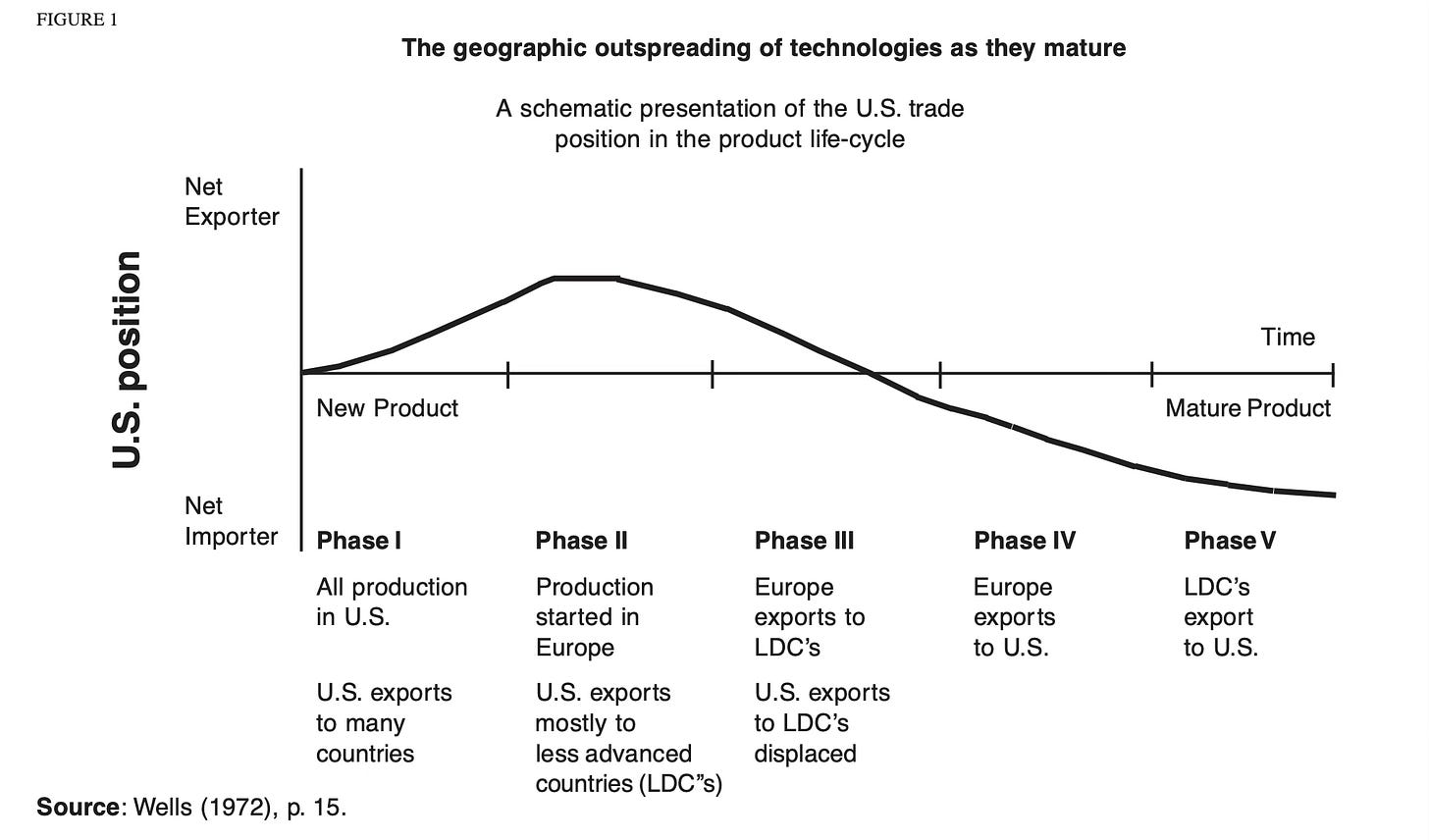

Perez cites professor Louis Wells, a Harvard economist, who (in his 1972 article) noted a repeating pattern of how manufacturing spreads geographically and how, in turn, it affects the U.S. trade position.

When a new generation of products is introduced, the U.S. is a net exporter with a decent surplus. It is in a position to provide export finance and pushes for free trade in search for new markets. Then, as technology transfer occurs, it inverts the picture: first Europe and later the lower income countries localise manufacturing and begin exporting products back to the States, so America turns into a net importer with a yawning trade deficit.

Very similar to what we can see now, the U.S. balance of trade in the second half of the 1960s was deteriorating rapidly. If in 1964, the U.S. had a trade surplus of over $6 billion, of about 1.1% GDP. By 1971 it lost $8 billion and the surplus turned into a deficit of about $1.5 billion. In 1972 it was expected widen further to $3.5 billion. American main trade partners: Canada, the European Community and Japan enjoyed the boon of the globalised trade system and fixed exchange rates giving their producers strong cost advantages.

As it has been doing until recently now, the United States in the 1960s shouldered most of the burden of containing communist expansion in Europe, where its NATO allies gained substantially from American military aid and joint defence infrastructure (an investment with a spillover effect that arguably dwarfed the impact of Marshall Plan) and in Asia, it waged war in Vietnam. Washington’s share of NATO defence spending topped 75%, greatly outstripping what its partners contributed as a share of GDP. Lyndon Johnson’s generous “Great Society” spending agenda, much like Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act and other expansionist programmes, further strained America’s fiscal position. The budget deficit widened, propped up by an ever-growing stock of public debt and its monetisation.

A newly elected Republican president, Richard Nixon, arrived in office with what looked very much like his own version of MAGA: putting America’s interest first. Much as Donald Trump would later do, he appealed to disgruntled white voters in the economically lagging South by vowing to restore “law and order”, which widely read as a coded pushback against the liberal progressivism many felt had gone too far. He also promised to rein in Washington’s borrowing binge and protect American businesses from what he saw as unfair competition by “ungrateful” allies.

Little wonder that Trump’s allies have embraced Nixon’s rehabilitation, spurring an outbreak of “Nixonmania” among his supporters. Trump himself is an admirer: in the 1980s, he and Nixon met on several occasions and exchanged warm letters, in one of which the young and ambitious real-estate magnate to be hailed the conservative veteran as “one of this country’s great men.”

In August 1971, in what would be later known as “the Nixon shock”, the U.S. President unilaterally dismantled the Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate regime by ending dollar-gold convertibility and imposed a 10% surcharge on imports to curb U.S. trade deficits and force the trade partners to negotiate. The shock sent the world reeling.

Much like now in 2025, America’s allies were dismayed. Ralf Dahrendorf, a German politician, captured the sentiment in a 1 September 1971 op-ed for The New York Times, writing that America’s partners were “shocked” and “stunned.” He went on to note that “the simultaneous announcement of new tariff and nontariff barriers which might add up to discriminatory import charges of 25 per cent or more is unprecedented in the recent history of world trade.”

Again, as with Trump’s tariffs in 2025, Nixon’s attack on the global trade system was also a “negotiation enabler” and “on-and-off” process. After months of haggling, the G–10 nations signed the so-called Smithsonian Agreement in December 1971, effectively restoring the fixed exchange rates system while allowing the US dollar to devalue. Yet it soon was broken too. In 1973, six members of the European Community agreed to peg their currencies together, leaving the joint exchange rate to the U.S. dollar floating to reflect “unpredictability” of the U.S. trade policy.

And then came the geopolitical pivot: détente with Moscow, a game-changing rapprochement with Beijing, laying the ground for what Niall Ferguson would later dub “Chimerica”, Sino-American economic symbiosis at the heart of the current (and ending now) techno-economic paradigm, and the 1973 oil crisis. The Nixon shock itself didn’t cause much of a direct damage to the global trade: in fact, despite exchange rates volatility and policy uncertainty it continued to expand. But the 1973-1975 recession and the subsequent stagflation certainly did.

Aligning boundaries and weaponising asymmetries

Mainstream neoclassical economists have typically labelled political events, be it trade blockades, sanctions or the election of unpredictable populists, as “external shocks,” treated much like an alien invasion or a typical “Black Swan” event that suddenly derails the economy. “Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition.”

In the Schumpeterian long-waves framework, they look less random. Game theory can even explain mathematically why and when economic and political actors might behave destructively. Consider the “frenzy” and “synergy” stages in Perez’s model from the the risk-slash-expected-return perspective: as a rising tide lifts all boats, the numerator (expected rewards from cooperation and participation in the game) perceived as high, while the denominator, uncertainty, perceived as low. Everyone buys into a system of deals and agreements, sometimes even accepting the lack of control and an asymmetric dependence, because the big payoff is worth it.

Then rapid change blurs borders: social and cultural shocks, such as urbanisation, cross-border movement of goods and people, leave people feeling deprived of boundaries. Mary Douglas, a British anthropologist, argued in her book Purity and Danger that people, especially those belonging to close cultures with rigid structures, find “transparent” boundaries unsettling; they perceive it as “impurity” that sparks a knee-jerk push for “restoring control.”

The rise of nationalists, populists, anti-globalists - you name it - is a typical “backward looking” solidarity reaction to the phases of rapid growth, when economic forces tear the social fabric, spur vertical and horizontal mobility and shake institutions. To meet that pent-up demand for “regaining control” among the “silent majority” politicians, from Nixon to Trump, pivot to the ideas of “security of supply,” the language of “order”, and building walls to closure the border from the outside source of hostile chaos encroaching the “purity” of civilisation.

As long as the tide keeps rising, most players remain in the game for fear of forfeiting future rewards. But once uncertainty swells and growth slows, cooperation frays.

The Overton window (the term named after Joseph Overton, an American political analyst, referring to a range of ideas deemed politically acceptable) opens wider, making room for what is often (mis)labelled “conservatism” or “populism,” legitimising calls for what was previously categorised as “unthinkable”. The “mainstream” part of the political spectrum erodes and the system polarises.

Those who control key resources begin to “weaponise” the asymmetry of dependency. So Nixon can unilaterally devalue the reserve currency, confident the Europeans can’t retaliate, and Arab states exploit their dominance in oil supply. Beneath the “political shock” label, or what could be seen by some as brinksmanship or “pandemic of madness”, lies a predictable logic: in the face of growing uncertainties and emerging cracks in the system, actors attempt to “align the boundaries of control”, i.e. reduce their exposure to external forces and use others’ dependencies on them as a weapon. Of course many of them, like, perhaps, Trump now, when taking on China, may miscalculate and underestimate the strength of the rival. It doesn’t change much.

When a critical mass of imbalances is accrued and the time of uncertainty is signalled by sometimes a merely symbolic action (like assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914 or the Nixon shock), the use of those weapons begin. It marks the entrance of the stages of “adjustment” or “turning points”. Like with Chekhov’s pistol hanging on the wall, which must fire in the last act, the odds of someone cutting the Gordian knot of imbalances are close to 100:1.

The biggest grey rhino is that we are now entering such a stage of about 10-15 years transition to a new techno-economic paradigm, and a series of painful adjustment, including “political turbulence” and a reset of institutions, is inevitable.

Chapter III. Transition and major shocks

So, if we take Carlota Perez at her word and assume we are transitioning from what she calls the “Age of Information and Telecommunications” to a new paradigm, most likely one powered by artificial general intelligence (AGI) and robotics, then what should we expect?

If history is anything to go by, it’s not gonna be a smooth ride. The last three such transitions, around the 1860–1870s, 1910s and 1970–1985 respectively, were anything but halcyon. When the age of steel and electricity began to supplant that of steam and railways in the latter half of the 19th century, there was a series of major conflicts (including the American Civil War) and the Long Depression. Then, as the era of oil, automobiles and mass production arrived, the world plunged into the First World War and a string of recessions. The most recent shift, half a century ago, was comparatively less bloody in the West, though not in many parts of Asia, but economically painful nonetheless.

But couldn’t this time be different? After all, history doesn’t necessarily have to repeat itself. People learn from the past; progress is meant to make us more civilised and sophisticated. Why can’t we simply skip the pain and scars? Let the world’s good and wise unite, rid us of belligerent narcissists, corrupt “stationary bandits” and reactionary thugs of all persuasions, iron out our differences and steer a smooth transition.

Tantalisingly, new breakthrough technologies promise a massive surge in productivity, meeting nearly all of humanity’s labour needs. “Machines of loving grace”, so the optimists insist, are expected eradicate poverty and make us healthier, wealthier and wise.

Crisis as inexorability

Yet the pace of adoption for any new technology is seldom uniform across regions and within societies. Every disruption makes some big winners and others painful losers. Groups’ interests diverge dramatically. As Mancur Olson, a prominent American economist and political scientist, explained, smaller factions and tactical interest coalitions tend to prioritise their own narrow aims over the common good. Once that sense of shared benefit fades in the face of change and uncertainties, those holding the stronger bargaining hand typically tend to resort to more assertive policies and threats. This correlation was observed statistically and has been debated for quite a long time by academics and political forecasters alike.

Firstly, the line between using the threat of violence in haggling and actually unleashing it often blurs faster than we tend to think: wars typically begin under the banner of “pre-emption” to avert “some greater evil” (typically the evil of your potential adversary striking first) before it’s too late. After all, no nation’s armed forces are supervised by an authority with the title “Ministry of Aggression”, they all are called the “Ministry of Defence.”

Secondly, new inventions can be directly weaponised or used to magnify the destructive power of existing arms. In the late 19th century, steel enabled heavier artillery, the “automobile and oil” era brought tanks and military aviation. The first who deploy breakthrough inventions and weaponise them gain strategic military advantage. It prompts dangerous arms races.

Thirdly, wars have proven to be convenient tools of political survival, legitimising “emergency” and “emergency powers” by rallying the public around the flag.

In their seminal work The Logic of Political Survival, Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and his co-authors introduce the ideas of a “selectorate” (the set of actors and agents who can influence the ascent and political survival of leaders) and a “winning coalition” (the subset among them whose support is vital). They explain how autocrats who hijacked weaker institutions in their less developed countries, with the narrower winning coalitions they need to please, are generally keener to go to war in the hope of rewarding loyalists with the spoils of victory.

Yet even in democracies with broader constitutional “selectorate” base, wars can tilt the scales of political survival by neutralising or even excluding from influencing decisions its significant parts. By invoking national security, leaders can suspend normal “checks-and-balances” and stifle opposition. Emergencies allow governments to grant themselves extraordinary powers, introduce war censorship and even, if need be, change the rules for elections or lift the limits on being re-elected, all under the pretext of defending the land. Even in systems that designed to represent many and require broad “winning coalitions”, wars can, at least temporary, empower the few who benefit from tighter control.

Donald Trump’s current “winning coalition” is on shaky ground. At home, his “war on the deep state” tests constitutional limits, and critics say it verges on abuse of office. That risk grows if he and his allies stand to lose everything, maybe even their own freedom, if he leaves power. In such a setting, a military conflict with a strategic rival ticks too many boxes to rule out as “unthinkable”.

Besides, Trump’s willingness to appease not only Putin’s Russia, with which, as critics claim, he has personal ties, but also, unexpectedly to many, Iran, by offering a soft, Obama-like deal, aligns with the theory of a looming war with China. The apparent goal to break the axis and isolate Beijing would explain a lot. The odds of an open clash with China, perhaps even before the 2026 midterm elections, may be, simply mathematically, much higher than many influenced by “normalcy bias” may now believe.

Crisis as a prerequisite

We are used to the axiom that cyclicality and crises are the bane of our economy. Smoothing the cycles out has been a dream of many, from Karl Marx to John Maynard Keynes. Nobody likes pain and policymakers tend to try to avoid crises at all costs. As in The Naked Gun 2½, a 1991 movie with Liam Neeson, the character of the U.S. president struggles to memorise his speech: “Recession bad, recovery good... I think I got that.”

Yet, downturns and crises perform the critical function of a catalyst of change, deployment of new technology and culling the outdated, making space for adaptation to the new and future growth.

Economic agents, individuals and firms alike, tend to cling to status quo, the skills and settings they are used to, even when they become uncompetitive and outdated so earnings no longer cover costs. Propped by subsidies, welfare payments, protectionist measures and raising debt at artificially low rates they mount liabilities and preserve inefficiency. It often takes severe economic pain to seek new skills, switch jobs, move places or adopt new technologies.

Milton Friedman once famously noted: “There is enormous inertia — a tyranny of the status quo — in private and especially governmental arrangements. Only a crisis — actual or perceived — produces real change.” The longer the status quo is propped up by “risk-averse” decision-making, the higher the cost of inevitable change.

Even at the stage of maturity of the outgoing “age”, the cost, risks and complexity of switching to a new technology are still onerous. Expected savings or gains from the switch are not big enough to justify the hassle and disruption. But a crisis abruptly alters the risk-reward equation. When the old way of doing business becomes prohibitively expensive, or plainly impossible, the deployment of innovative solutions turn into a lifesaver. Recessions therefore play an important role of a “pit-stop” of development, when the economy is rebuilt and the outdated structures are “pruned out” in an important process of “cleansing”.

During the mid-2000s energy crunch, fracking, which had been a relatively mature technology for about a decade, shifted almost overnight from a niche segment to a mainstream method sparking the “shale revolution”. Likewise, when COVID-19 struck, e-commerce, QR codes and video calls went from niche segments and toys for tech geeks to the staples of everyday life.

Transition from one techno-economic paradigm to another requires a crisis much deeper and longer than the one caused by the lockdowns.

As a real estate developer, Trump knows the drill: it takes bringing down what’s aging or dilapidated to make room for something new. That process can’t avoid pain or controversy, since some stakeholders will always want to preserve the status quo. A crisis, “actual or perceived,” is often what breaks that resistance to get demolition done.

Chapter IV. Brave new world

Last time, it was the famous Paul Volcker who opened and closed the show. In the early 1970s, as an undersecretary of the Treasury and Nixon’s adviser, he prodded the President to trigger a crisis and revolt against the “tyranny of the status quo.” Around the same time, intellectuals warned of “the limits to growth,” and the post-war booms in Europe and Japan were losing steam. The Nixon Shock set everything in motion; the ensuing oil crises sped up the demolition. The decade of stagflation and geopolitical readjustment unfolded.

Then, in the 1980s, Volcker finished what he started with the famous disinflationary “shock therapy” which caused a W-shaped recession. Its “cleansing” effect cemented a new paradigm and carved out a fresh global division of labour, the one that endured until recently and now being torn down.

Neither Nixon nor later Ronald Reagan, nor Volcker himself, had a grand plan for the transition. Its trajectory is visible only in hindsight; in real time, the main players simply handled each crisis opportunistically. As Hegel noted, new ideas and institutions are sometimes brought about by “force and wrong.” Trump’s “reckless” and “incompetent” trade wars are indeed a form of that wrong. Yet, similarly to the Nixon shock they are needed to bring about change.

The outgoing epoch

So, what is now being demolished?

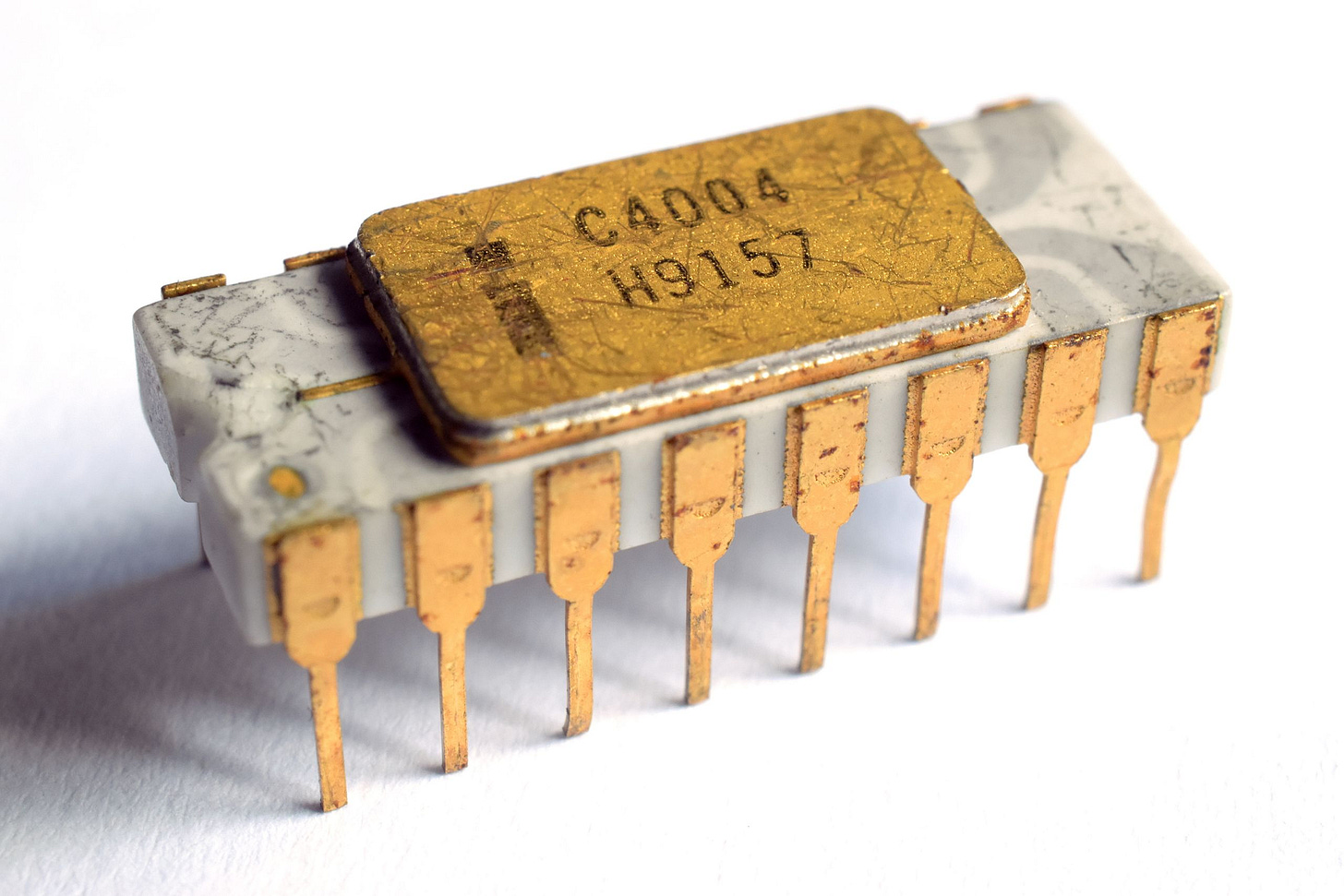

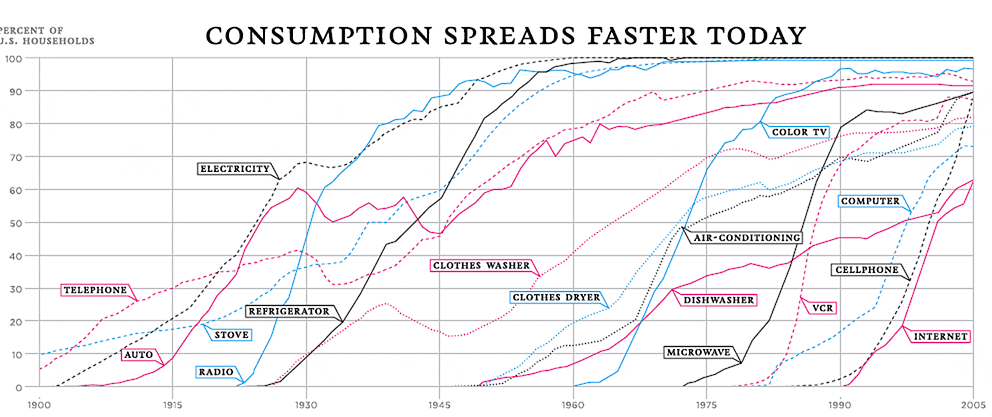

The “Age of Information and Telecommunications,” or, in Klaus Schwab’s wording, “the third industrial revolution” was evidently sparked 55 years ago by the invention of the first semiconductor-based microprocessor. Carlota Perez uses the term “big bang” to describe such catalytic moments. Within just a few years, personal computers burst onto the market, and by the end of that transitional phase in 1984-1985, around one-fifth of U.S. workplaces had installed a PC and every tenth household had a computer at home. Then along came Internet.

But beyond the textbook narratives about the history of computing and its impact on our life and work, this “electronics” shift sparked a dramatic rethink of business processes. Ford’s linear “assembly line” gave way to what is often called “modular logic” or “modularity,” in which autonomous modules, much like building blocks, can be produced independently and then combined in various ways, creating a wide array of finished products and their customised models.

Stationary, hierarchically organised megacorporations, integrated from top to bottom (and left to right), were gradually outcompeted by “fluid” and flexible groups, multinationals or clusters insourcing or outsourcing risky R&D and product development ventures to project teams and small startups. The French researcher Christophe Midler called this phenomenon “projectification.”

The megacorporation “pyramid” was dismantled to a “flat Earth” of distributed hubs — a global “Legoland” of building blocks. Each hub could then exploited its comparative advantages (such as cost of labour, capital, energy or location) to compete worldwide, enhancing productivity through specialisation. A similar leap occurred in the 19th century, when railways broke open hitherto closed regional markets, spurring economies of scale.

As “modular” and complex supply chains stretched across the globe, they required a very specific model of globalisation. First, trade barriers had to be minimal and predictable, ensuring frictionless flow of goods. Second, free movement of capital was vital for investment in offshoring manufacturing and transferring technology. Yet labour mobility was, by contrast, curtailed: electronics assembly remained highly labour-intensive, cost-sensitive companies relied on cheaper overseas workers—and that advantage would have vanished had they migrated en masse to richer countries. In short, goods and capital roamed freely, while people stayed put.

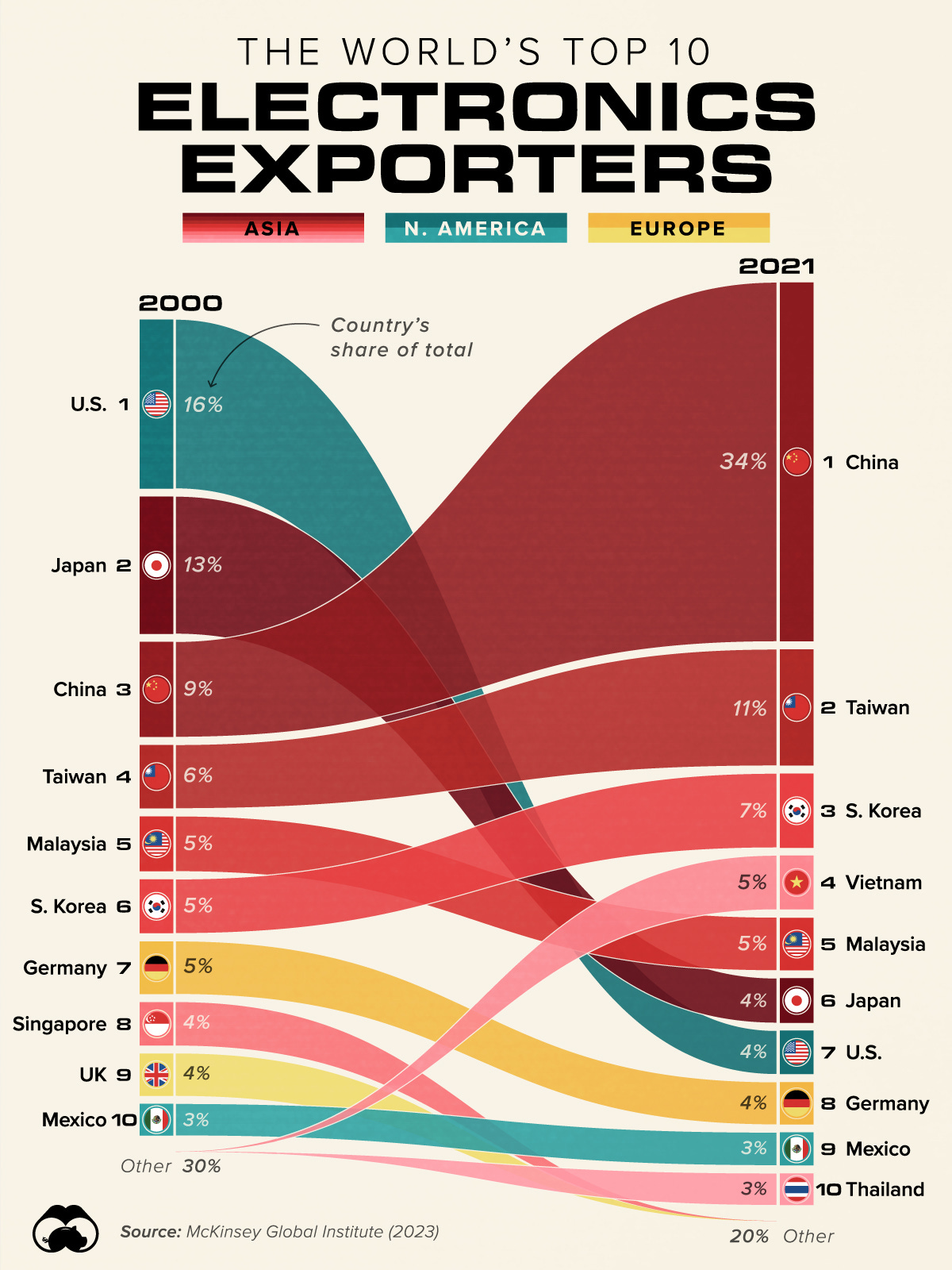

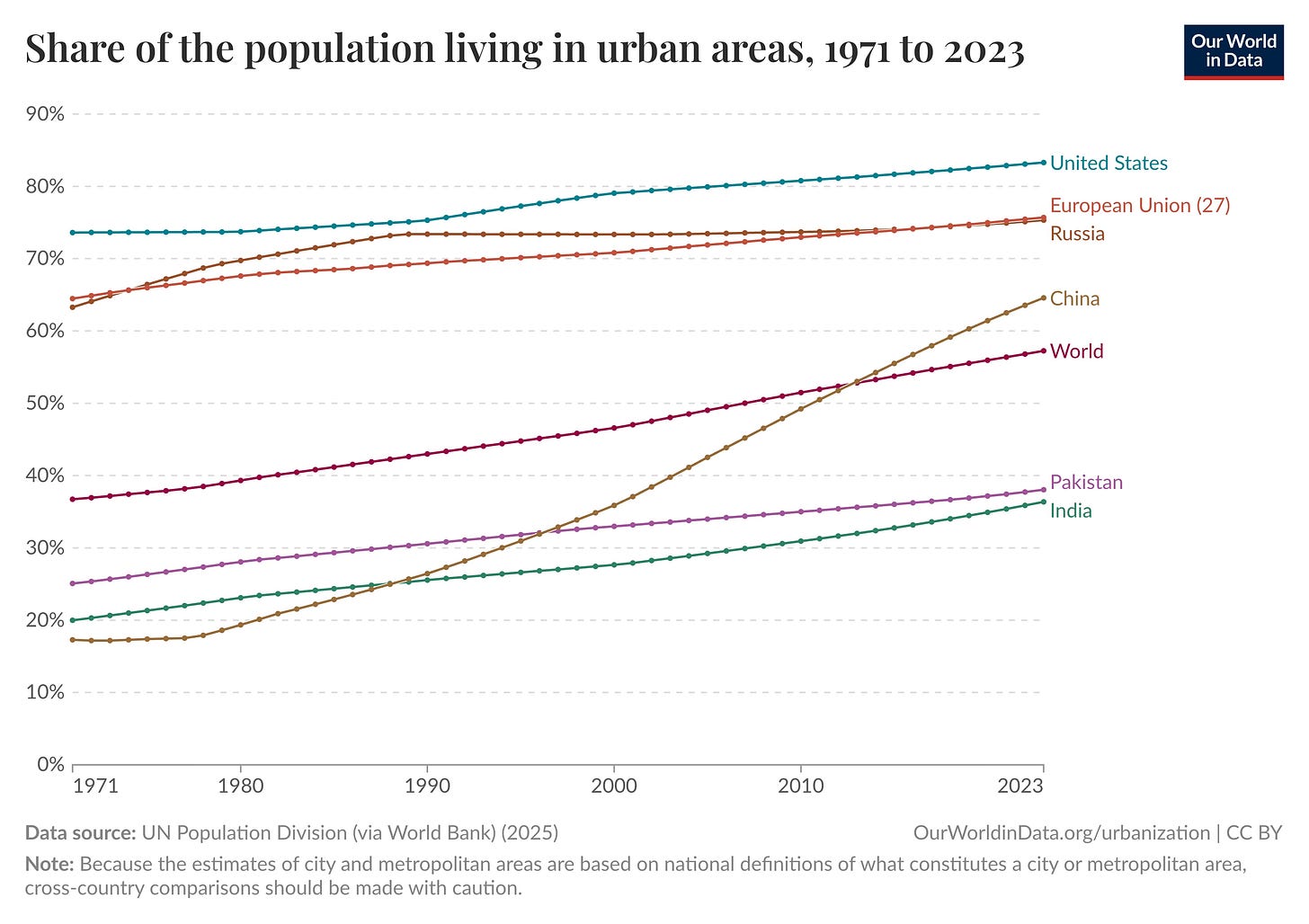

And the resulting division of labour, specialisation of the parts of the world, was no less peculiar. Lower-income nations, chiefly in Asia (China above all), obviously supplied vast pools of cheap labour, backed by rapid urbanisation and internal migration. One might assume higher-income economies would naturally, in turn, supply the capital. Except they often did not: the United States and most Western Europe (with a notable exception: Germany and Netherlands), in fact, became net importers of it. Capital was instead sourced from the global savings glut with a steadily increasing amount of dollar liquidity chasing limited supply of financial assets, thus driving down real interest rates, inflating bubbles and boosting a pile of debt.

Instead of playing its usual role from earlier long waves, exporting both goods and capital, the United States, after the Volcker shock, all but scrapped its heavy industry and labour-intensive manufacturing. It reinvented itself as, firstly, a global marketplace for capital (via its financial sector), secondly, a factory of intangibles: intellectual property (from R&D to entertainment), know-how and global security assurances (MIC and geopolitical clout) and, thirdly, a global consumption machine fuelled by ever growing debt and appreciation of paper wealth nominated in the world’s reserve currency.

On the other hand fast urbanisation in China spurred massive residential and infrastructure buildout, starting a new global commodities super-cycle that proved both boon and bane for resource-rich regions. China’s construction sector at some point would consume around half the world’s steel, cement, nickel, copper and aluminium. This, in turn, propped unprecedented growth in consumption in the raw materials exporting countries, including Russia and the Middle East. The “double bubble” of 1999 and 2008, in Carlota Perez terms, has cemented the architecture.

One often-forgotten yet important repercussion of the labour-cost-arbitrage offshore manufacturing model is that it also effectively encourages waste. Since domestic labour is far more expensive, everything related to maintenance or repair of imported goods becomes burdensome, especially compared to simply buying a new item. Each US$1 spent on a single-use, “instant” discount product bought on Amazon can often carry more than a dollar in hidden waste-disposal liabilities, including indirect health and environmental costs.

That is the system we are now used to and consider normal.

The main value drivers in such a system were ever expanding consumption, labour costs arbitrage (which helped to break the link between monetary and consumer prices inflation: labour wages and consumer prices were divided by the state borders) and R&D powered by the abundance of cheap capital and associated financial bubbles. Very similar to how the financial bubbles of the fast helped to build canals, ports and railway networks.

The globalisation model we are accustomed to relies on an intricate web of cross-border supply chains that capitalise on cost disparities, mainly labour, alongside technology transfer and deeply unbalanced, systemically unsustainable trade interdependencies. Physical flows of commodities and manufactured goods, underpinned by vast infrastructure networks, form its foundation.

What is changing?

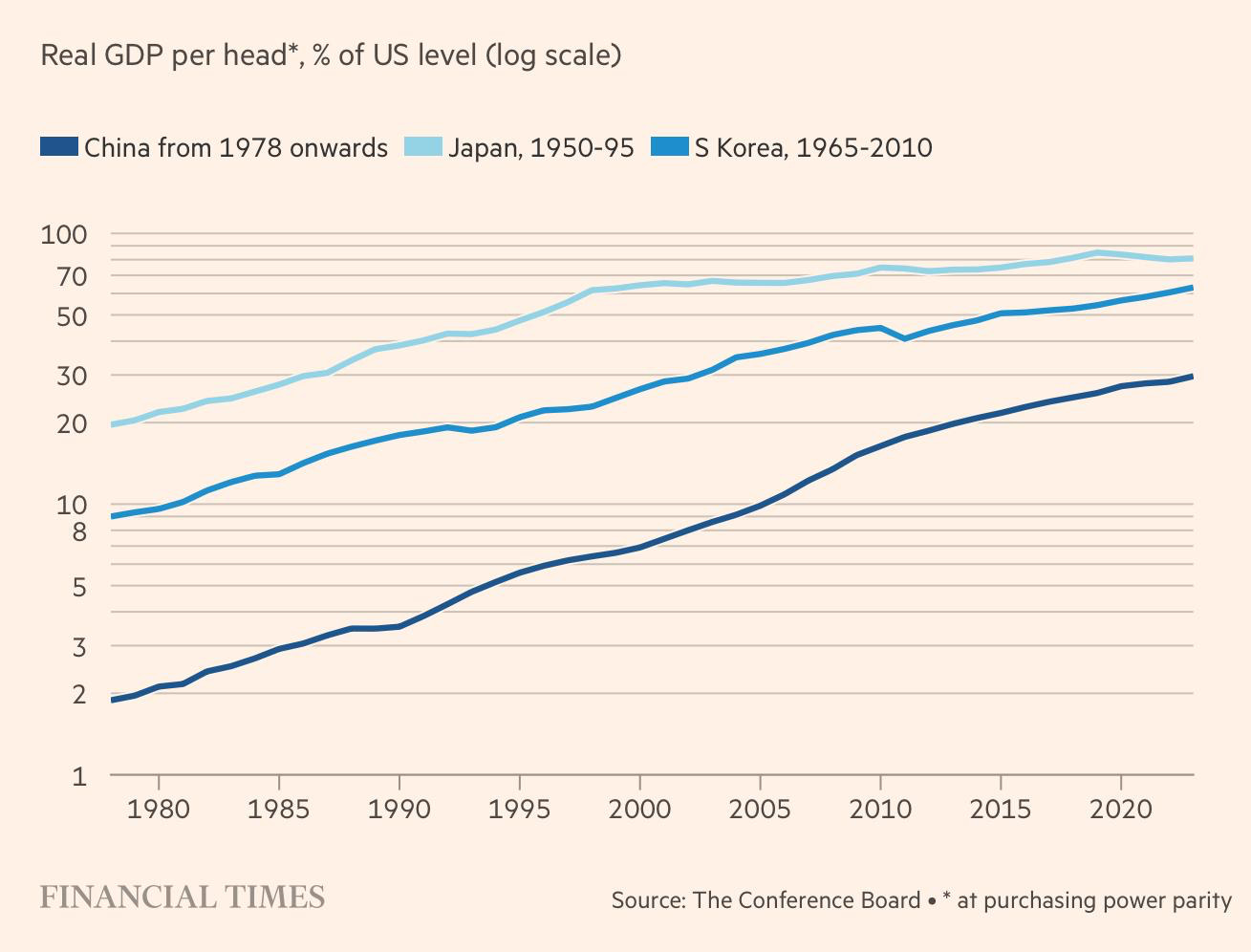

One, rather commonplace, observation is that the current system has reached its fundamental limits. The labour-cost-arbitrage engine is running out of steam as rapid technology transfer and catch-up growth narrow income gaps. China is no longer a low-income nation; it’s an “Asian tiger” on steroids, closing in on American income levels (in purchasing-power terms) far faster than its predecessors ever did.

What many call China’s “housing bubble” is, regrettably, more than just a frothy speculation cycle. Earlier massive housing buildout was fuelled by urbanisation and a mushrooming demand for new homes. But as urban demographic growth slows—on track to plateau soon—that demand is set plummet. This marks a structural shift not only for China but for the entire global commodities market, since no other economy can replace its colossal appetite for raw materials and energy. As the super-cycle subsides, so do the outsized revenues that commodity exporters once enjoyed.

So, the second pillar of the current paradigm—consumption—is on shaky grounds too. In the developed world it was mainly supported by debt, which has reached unsustainable levels. In the emerging markets it was underpinned by high commodity prices.

But perhaps more importantly, the “big bang” moment of the next long cycle is already upon us. Its picture remain hazy, like in a photograph emerging in the developer fluid, but we are slowly beginning to see the contours of the new paradigm taking shape.

Self-evident, verging on cliché, is that the next epoch will hinge on artificial intelligence. But how AI will rewire the system and reshape the global economy remains far less clear. Most predictions split into two extremes: one side conjures Frankenstein-style dystopias where androids steal not only human jobs but eventually take over the world; the other offers dull extrapolations as if AI was just another “productivity boosting” office gadget while the business architecture and value chains would remain more or less unchanged.

Yet it will change. When horses gave way to cars and tractors, it did not merely eliminate stable lads and ostlers while boosting farm productivity. It also spurred job creation in oil extraction and refining, logistics, and Walmart-style retail.

Without going into detail (this merits its own article, if not a book) it appears that in a world of autonomous AI agents and robotics, human jobs will shift from areas of low transactional costs (as Oliver Williamson would say) to those where such costs remain high. Put simply, humans will take on roles involving decision-making in the context of higher stakes and greater uncertainty, while AI-powered automation will first take over standardised business processes where outcomes are more predictable.

The former, human-centred services, which include everything to do with “care” (such as healthcare, eldercare and childcare) as well as government, security and defence—areas where AI agents and automated assistants must remain under tight supervision. Meanwhile, the latter would encompass new manufacturing (robotics, additive technologies, circular production and lifetime materials management, in which goods are basically rented out and then returned for recycling), as well as more standard customer support roles, agriculture, and so forth.

Combined with an energy transition—renewables, industrial-scale storage, advanced nuclear, and possibly hydrogen—this points to a future in which everything from electricity to microchips, from food to financial services and healthcare, is produced and consumed locally. Physical cross-border trade would not vanish, but its share of global GDP would likely fall well below current levels.

On the other hand, a ubiquitous “singularity” implies that research and development could pivot away from extracting finite resources toward inventing new ones from what is already at hand. Over a century ago, the American economist Simon Patten argued that scarcity is a myth, because resources are invented, not discovered. Oil, for instance, held little value before the combustion engine. And before Fritz Haber’s ammonia process, agriculture depended on natural fertilisers, like guano, excrements from tropical seabirds, turning a foul-smelling byproduct into a source of sudden fortune for its traders. Previously, lead times of substitutes for “scarce” resources were measured in decades. In the age of AI it could be reduced to years. It would turn conventional geopolitical thinking upside down: even control over Trump’s favourite rare earth minerals would not be that significant.

At the same time, the power of new technologies and our reliance on them will make the system ever more fragile and exposed to external threats. In a world where almost anything can be weaponised, all things “security”—physical, cyber or otherwise—are poised to see their value soar.

Considering all of the above, it appears all but inevitable that in the upcoming “AI age” once globalised world economy will split into competing multipolar blocs, adhering to a new form of trade nationalism. Where the old system encouraged technology transfer, the new one will work to fence off “technology leakage,” prioritise security, and slash unnecessary trade interdependence to a minimum.

When this transition and readjustment finally runs its course—around 2040, say—a new globalisation model is likely to emerge, fostering international cooperation as humanity grapples with the unavoidable impacts of climate change (including mass migration amid environmental crises), the threat of new deadly viruses and other common challenges. But it will take time to get there.

Chapter 5. The storm ahead

Both economic fundamentals and the logic of policy decisions point to a “new 1970s” scenario.

The next global crisis and recession, perhaps as soon as next year, will have a very specific historic function. It will have to catalyse a deployment of new manufacturing (robotics, etc.) to replace the offshoring model, especially in its low-tech, labour-intensive segments. That shift requires prices for manufactured goods to be high enough and interest rates low enough to justify the cost of switch.

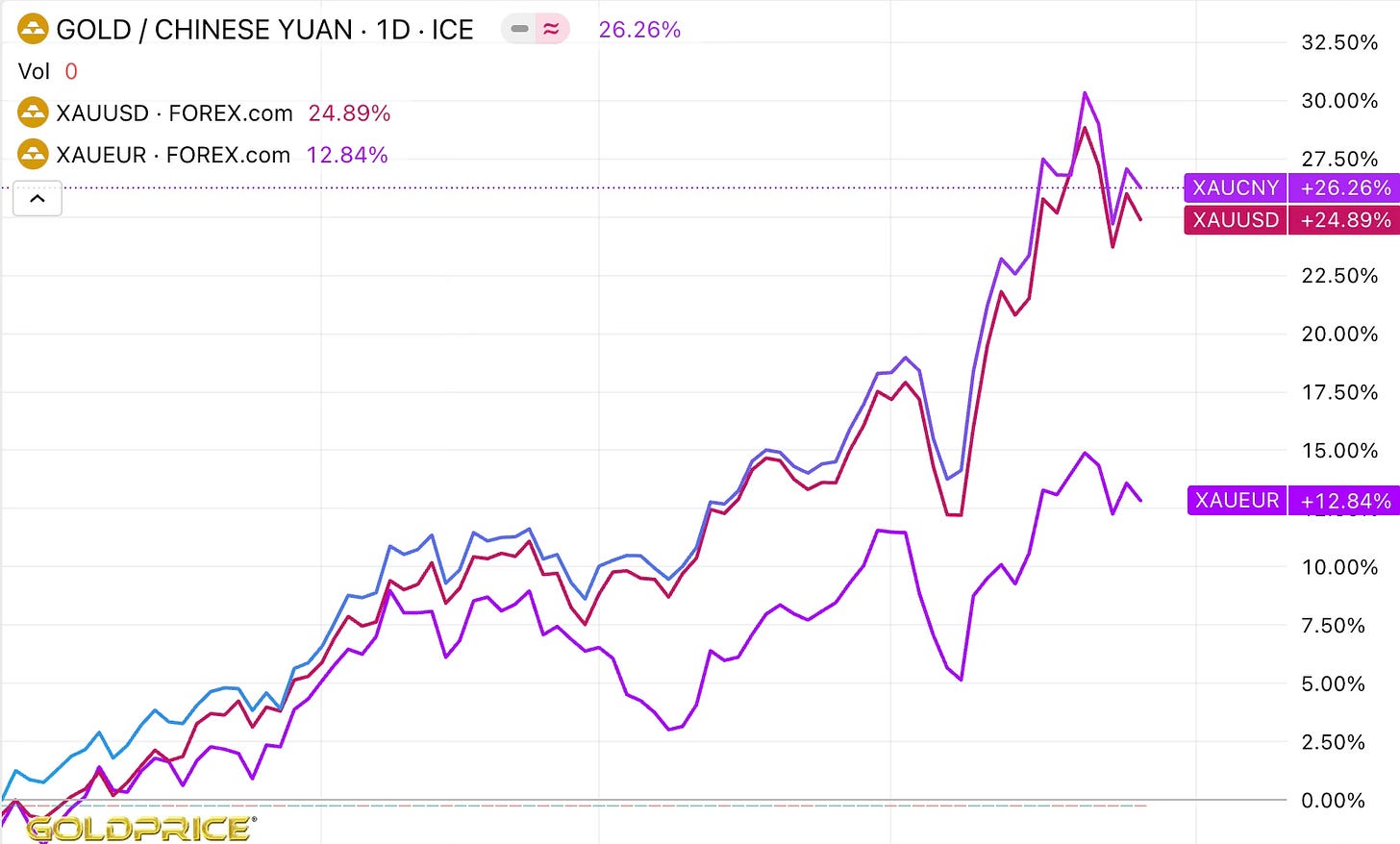

With Jerome Powell leaving and Trump appointing a more compliant Fed chair—much as Nixon replaced Bill Martin with the dovish Arthur Burns in 1970—monetary policy could be pushed to accommodate these goals. Even if the worst fears about tariffs never fully materialise, ongoing uncertainty over global trade, plus lower rates, would lift prices. At that point, what began as a tariff war might well transition into a full-blown currency war, triggered by a depreciating dollar.

China, America’s main adversary in the tariff war, may end up taking a “pre-emptive” shot in that currency battle, devaluing yuan and adopting an expansionist strategy. The Communist Party has already promised broad support for exporters hit by U.S. duties—likely just the start of a much larger stimulus push. Meanwhile, amid all export uncertainties, Beijing has few options but to speed up boosting domestic consumption. Yet with households’ historically high savings rates, just handing out subsidies for rice cookers and microwaves may not be enough. Achieving genuinely higher spending could require significantly higher inflation and negative real interest rates to discourage saving.

In this climate, Europe’s bid to rally “the rest of the world” spurned by Trump and salvage the fading free-trade model may prove costly. The euro has already risen by about 12% against both the dollar and the yuan, making Eurozone goods 12% pricier abroad. Should Brussels double down on its leadership ambitions, the euro could become even more attractive as a reserve currency, pushing it higher still—and hurting exporters more. Meanwhile, cheap “rest of the world” imports would flood European markets in the absence of trade barriers. Sooner or later, to avert a sharp downturn, the ECB would have to slash rates and inject liquidity, which would coincide with unprecedented fiscal expansions on defence, infrastructure, and state aid. That, in turn, would drag Europe into a “beggar-thy-neighbour” inflationary race— from a position that is weaker and more exposed.

This policy-driven turn toward pro-inflationary trend will likely be amplified by two deeper fundamental factors: what British economists Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan called “the great demographic reversal”, which ends the decades-long era of demographic tailwinds, and a yawning skills gap in the context of the AI revolution. Both will strain labour markets (push wages up for shrinking labour force capable of filling new economy jobs) and increase the burden of social spending to help those redundant and retired to maintain the standards of living.

Under the weight of huge private and public debts, central banks will face immense political pressure, since conventional anti-inflationary tools like rate hikes and quantitative tightening risk triggering a wave of defaults. As a result, they may be forced to tolerate higher inflation for longer than many might think. On the flip side, it, over time, would erode the real value of debt, albeit by penalising creditors and savers.

In lieu of a conclusion

Donald Trump came of age as a businessman in the economic storms of the 1970s, amid high inflation, energy shocks and steep downturns. Eerie parallels with those times are no coincidence: we are about to enter a spell of flux and painful adjustment in a paradigm shift of a similar, if not greater, magnitude. Trump knows from his business experience that in a room of “grey rhinos”, those who control the timing of a crisis can use it as an opportunity. He knows how not to “waste a good crisis”. He used bankruptcy laws six times in what is called “strategic bankruptcies” to profit from reducing debt. Now he seems to be instigating a “strategic bankruptcy” of the global economy.

He doesn’t seem to have a grand vision for this transition and, even if he does, typically the agenda of demolishers seldom gets implemented. But, as at least some hint, his inner circle might profit from the current markets turmoil knowing his next “erratic” turn.

The previous “demolisher”, Richard Nixon, was forced to leave before the end of his second term. Surely, there will be no shortage of attempts to remove him and reverse the course as it is a healthy immune reaction of the system. It may prove difficult. Asked about the difference between him and Nixon, Trump once said: “He left. I don’t leave. A big difference.” But even if he is ejected or otherwise “deleted”, the Overton window is smashed with a wrecking ball: we are living through what would once have been unthinkable. The system could be patched temporarily, but in a longer run “the eggs” of the outgoing paradigm could not be unscrambled.